Why Psychology Hasn’t Had a Big New Idea in Decades

Can our field get its act together?

A guy named Thomas Kuhn gave us an idea: Every scientific field has its own paradigm — a set of assumptions, methods, and commitments that shape how scientists think. Paradigms frame what counts as a valid question, suggest what methods make for a meaningful study, and determine how problems are solved.

A science needs a paradigm because we underrate a simple fact: there are an infinite number of things you can study and infinite ways to study them. Without some sense of which things are in bounds and which things are out of bounds, you end up totally confused. "A dog's bark is louder than a cat's meow, is that important?" "I kept track of how often I think about giardiniera peppers and it's 1.4 times a month, is that something?" "The maximum speed of my car doesn't change when I paint it different colors, maybe that's relevant?"

Without a paradigm, all you have is a topic. But a paradigm gives you shape. Chemists agree that mass can’t be created or destroyed, so when you’re studying chemistry, you make sure to weigh everything very carefully. In the physics department, they measure how much energy they put behind a cannonball. They don’t measure what color they painted it.

Under normal conditions, scientists working inside a paradigm don’t question these commitments any more than Formula 1 drivers question the fact they're about to race cars instead of bobsleds. Instead, the common language of the paradigm makes it easy to work together, make sense of the world, and go really really fast.

Since a paradigm lets you go so fast, you might not notice you’re inside one at all. Scientists often work inside a paradigm without having any idea what a paradigm is. They might even deny they're doing any such thing. But you actually can’t get away from this. "Paradigm" is a description of what your community assumes and values; you have one whether you like it or not.

For better or worse, no paradigm is perfect. Over time, people run across observations that don't fit neatly into the framework. Kuhn called these "anomalies”. At first, scientists assume that these are interesting puzzles that will eventually be solved using current methods, so the anomalies are downplayed or ignored. But as the list of unsolved problems grows, doubts about the paradigm begin to spread.

Anomalies do more than just accumulate, they clash with the deeply held commitments of the paradigm. And they’re more than just awkward, anomalies eventually make the paradigm’s commitments impossible to defend. When anomalies can’t be ignored any longer, the science enters a period of crisis that ends only when the old paradigm collapses, and a new one takes its place.

When a science switches out its old paradigm for a new one, we call it a scientific revolution. This isn’t “cute” or “heartwarming”, sciences only do this when they’re in extreme distress.

Paradigms shape everything scientists do and think, so the revolutions that overthrow them are profound. The new paradigm doesn’t just answer the old questions in a new way—it changes how scientists think about their problems. It redefines what details are important, how you measure success, and what truths are worth pursuing.

A paradigm shift is like going from playing checkers to playing chess. Oh, you thought there was one kind of game piece and they all behave the same way? No, there are six different kinds of pieces, and they follow different rules. Some can only go forward, some can jump over other pieces, and some cause the game to end if they get captured.

This may sound silly, but in the chemical revolution we went from thinking there were 4-7 elements to thinking there might be dozens of elements. Chemists went from thinking there was one kind of air to having to invent a new word for the quickly growing category of air-like substances, AKA the category of “gas”.

So as a psychologist, I can’t help but spend some time thinking about psychology’s next paradigm.

The State of the Art

Generously, the current paradigm in our field is cognitive psychology. This basically boils down to, “perhaps the mind is like a digital computer”.

Ulric Neisser, the psychologist who wrote the book Cognitive Psychology, asks us to “consider the familiar parallel between man and computer”. He tells us,

The task of a psychologist trying to understand human cognition is analogous to that of a man trying to discover how a computer has been programmed. In particular, if the program seems to store and reuse information, he would like to know by what “routines” or “procedures” this is done.

…

Although a program is nothing but a flow of symbols, it has reality enough to control the operation of very tangible machinery that executes very physical operations. A man who seeks to discover the program of a computer is surely not doing anything self-contradictory!

This particular framing is a defense against psychology’s previous attempt at a paradigm, behaviorism. Hardline behaviorists argued that because behavior is the only thing that can be observed, behavior is the only part of psychology that can be studied scientifically. You can’t observe a thought, so you can’t possibly measure it or run studies on it. Behavior only.

Cognitive psychology was a direct reaction to these ideas, and part of why the cognitive revolution was successful is that the computer, so obviously full of programs and subroutines, made it respectable to speculate about thinking again. Neisser says:

There were cognitive theorists long before the advent of the computer. … But, in the eyes of many psychologists, a theory which dealt with cognitive transformations, memory schemata, and the like was not about anything. One could understand theories that dealt with overt movements, or with physiology; one could even understand (and deplore) theories which dealt with the content of consciousness; but what kind of a thing is a schema? If memory consists of transformations, what is transformed? So long as cognitive psychology literally did not know what it was talking about, there was always a danger that it was talking about nothing at all. This is no longer a serious risk. Information is what is transformed, and the structured pattern of its transformations is what we want to understand.

Cognitive psychologists, or at least the ones who think about such things, certainly feel that this was a scientific revolution in Kuhn’s terms. In the 2014 Introduction To The Classic Edition of Neisser’s book, the psychologist Ira Hyman wrote:

Much like political revolutions, scientific revolutions need rallying cries. The cognitive movement was a scientific revolution and [Neisser’s book] Cognitive Psychology became the rallying cry for the cognitive revolution. In the 1950s and 60s, Psychology needed a scientific revolution. In Kuhnian terms, the field was ready.

Before behaviorism, psychology passed through what I can only describe as “early psychology”, a period where everyone was obsessed with the words “consciousness” and “introspection” — even though as far as I can tell, none of them agreed what those words might mean.

Less generously, psychology doesn’t have a paradigm and never has. My friend Adam Mastroianni makes the case for this position in his essay, I’m so sorry for psychology’s loss, whatever it is:

Psychology doesn’t exactly have a paradigm; we’re still too young for that. But we do have … proto-paradigms. We’re currently stuck with two proto-paradigms that were once useful but aren’t anymore, and one proto-paradigm that was never useful and will never be.

The first of the formerly useful [proto-paradigms] will be familiar: this whole cognitive bias craze. Yes, humans do not always obey the optimal rules of decision-making, and this insight has won two Nobel Prizes. …

The second formerly useful proto-paradigm is something like “situations matter.” This idea maintains that people's contexts have immense power over their behavior, and the strongest version maintains that the only difference between sinners and saints is their situations. …

The third proto-paradigm has never been scientifically productive, and won't ever be. It's also a little harder to explain. Let's call this one “pick a noun and study it.”

I’m with Adam. Despite some honest attempts, psychology has never had a paradigm, only proto-paradigms. We’re still more like alchemy than chemistry. And we won’t be like chemistry until we have our first paradigm.

This leads us to the obvious question: how might we go about getting our first paradigm?

Active Leads

Thomas Kuhn was trained as a physicist. He had three degrees from Harvard, all of them in physics. Physics has had a paradigm since the Ancient Greeks, so the question of where a science gets its starter paradigm was not very natural to him. Kuhn was mostly interested in revolutions from one paradigm to another.

On top of that, Kuhn’s first book was about the Copernican Revolution in astronomy. If anything, astronomy has had a paradigm for longer than physics has! In Kuhn’s experience, sciences always have some kind of paradigm waiting when you show up, and the main question is why there’s this cycle where they sometimes throw out the old one and bring in a new one.

The political metaphor, which he uses when discussing these ideas, doesn’t help. Political revolutions are always conducted in reaction to an existing government and always replace that government with a new one. Where the state got its first government is a different kind of question entirely.

As a result, Kuhn didn’t say much about how a science gets its first paradigm.

But he did say a little. In the introduction to The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn talks about how the pitiful state of psychology is part of what inspired his ideas about paradigms in the first place. He mentions “the controversies over fundamentals”, “the number and extent of the overt disagreements about the nature of legitimate scientific problems and methods”, and so on. He could tell that psychology was conspicuously missing something that was not missing in astronomy, physics, chemistry, or biology.

In a later essay, Kuhn said,

There are many fields—I shall call them proto-sciences—in which practice does generate testable conclusions but which nonetheless resemble philosophy and the arts rather than the established sciences in their developmental patterns. I think, for example … of many of the social sciences today.

So it’s clear that Kuhn always had psychology in the back of his mind. However, when it came time to give advice about how we might get out of this hole, he was pretty unhelpful. He said:

I conclude, in short, that the proto-sciences, like the arts and philosophy, lack some element which, in the mature sciences, permits the more obvious forms of progress. It is not, however, anything that a methodological prescription can provide. Unlike my present critics, Lakatos at this point included, I claim no therapy to assist the transformation of a proto-science to a science, nor do I suppose that anything of the sort is to be had. If, as Feyerabend suggests, some social scientists take from me the view that they can improve the status of their fields by first legislating agreement on fundamentals and then turning to puzzle-solving, they are badly misconstruing my point.

Let’s start with the parts I agree with. Kuhn is right that trying to force a paradigm is a mistake. When people try to legislate agreement, you get unforced blunders, like saying that Pluto isn’t a planet.1

But I think he’s wrong that nothing can be done. I think there are many things we can do if we want to kickstart the revolution. If nothing else, we can keep ourselves aware that it’s a possibility.

This is part of why I’m so interested in the transition from alchemy to chemistry, even to the point of sometimes trying alchemy experiments for myself. I think the alchemists didn’t have a real paradigm — alchemy was a proto-science. But when a paradigm was discovered, that gave us chemistry. This makes the transition from alchemy to chemistry one of the few examples of a science getting its first paradigm that’s actually well-documented.

Whether he means to or not, Kuhn does give us a couple of leads. In my opinion, here are the main two: 1) most of the time, the new paradigm is an old idea that’s brought back from the archives, and 2) a change in paradigm usually goes hand-in-hand with some kind of change in scope.

Old Hats

Kuhn points out that new paradigms usually come from old ideas, dreamed up back in some misty past, and resurrected only when the field is in crisis. “Often a new paradigm emerges,” he says, “at least in embryo, before a crisis has developed far or been explicitly recognized.”

Sometimes the proposal was developed during the last crisis, but was passed over at the time:

In cases like these one can say only that a minor breakdown of the paradigm and the very first blurring of its rules for normal science were sufficient to induce in someone a new way of looking at the field.

Sometimes the proposal was invented when the field wasn’t in crisis at all, so the idea of switching to a new paradigm seemed crazy at the time:

The solution [to many crises] had been at least partially anticipated during a period when there was no crisis in the corresponding science; and in the absence of crisis those anticipations had been ignored.

The new paradigm isn’t drawn directly from the void. Instead, it’s usually an idea that was discussed, dismissed, and later called back into service. Every science has a few benchwarmers, some of them warmer than others. Or occasionally, it’s a similar idea from a neighboring science.

Psychology is pretty young as far as sciences go; our bench is not all that deep. Unlike physics and astronomy, we can’t just dig down and find a different set of foundations laid out 2000 years ago by the Ancient Greeks. But we can look back to previous eras of crisis, go through their waste bin, and try to figure out if any of the ideas they passed over still have some juice.

Scope

A new paradigm always means a new scope for the field.

Early psychology was all about “consciousness” which was often studied through introspection. If that sounds impossibly fuzzy, to the point where you have a hard time believing it, I can’t blame you. But here’s William James delivering the same message with insane confidence (emphasis in the original):

Introspective Observation is what we have to rely on first and foremost and always. The word introspection need hardly be defined - it means, of course, the looking into our own minds and reporting what we there discover. Every one agrees that we there discover states of consciousness. So far as I know, the existence of such states has never been doubted by any critic, however sceptical in other respects he may have been.

With this set of commitments, the natural scope of psychology was human beings. It’s not clear if other animals are conscious, and even if they are, you can’t ask them to introspect about their experience and report back. So you couldn’t do psychology on mice and dogs.

After the proto-revolution that gave us behaviorism, the scope shifted. Introspection was out, and behavior was the only law. Suddenly, animals were acceptable research subjects for psychology.

In fact, animals were now better research subjects than humans. Behaviorists believed that all of an organism’s behavior came from the wiring between stimuli and response, associations formed over a lifetime of experience. This meant that any experience outside the lab would mess with your research. If the organism had ever encountered a stimulus before, it might have already formed some associations.

The ideal research subject had to be raised in a controlled environment from the moment of birth, and you weren’t allowed to do that with humans, at least not until the glorious behaviorist revolution was complete. So with the exception of a few infamous experiments involving human infants, behaviorists found that in the meantime it was best to confine themselves to studying animals, especially rats and pigeons. This is where the stereotype of psychologists studying rats in mazes comes from, which persists even though that stereotype is more than a generation out of date.

After the cognitive revolution, thinking was back in. Humans mostly, but not entirely, replaced animals as the subject of serious psychological research.

It’s clear why humans were acceptable again, but I don’t really understand why we stopped studying animals. To a cognitive psychologist, both human and animal minds are kinds of programs, or computers, and you can run basically the same studies on either. So why did we switch almost entirely back to people? Here are some theories:

Social psychologists, who did pretty well riding the wave of the cognitive revolution, wanted to study social relationships. Humans arguably have more complex social interactions than other animals, and social psychologists were interested in social questions very specific to humans, like “can we cooperate well enough to avoid nuking the planet?” For them, studying dogs or mice was a non-starter.

We are also, I think wrongly, paranoid about anthropomorphising animals. There’s this superstition that it’s unscientific to speculate about whether a rat working her way through a maze is having a good time. You have to frame the minds of animals in terms of behavior, or in terms of hormones, or else it isn’t “rigorous”. Meanwhile it is entirely scientific to hand a human a scrap of paper that says I AM ENJOYING THIS DAY 1--2--3--4--5--6--7 and treat their response like it came from a particle accelerator.

Another answer is more mundane. Today, the most common research method is the survey. These weren’t an option under behaviorism, but when behaviorism fell, they became an acceptable method again. Surveys have many advantages, but one drawback is that it’s surprisingly hard to give a research survey to frogs, birds, or dolphins. This also favored human subjects.

And of course, the most common research subject today is not just any human, it’s a very specific kind of human: the undergraduate psychology major at a top US research university. These subjects are special because they’re really close at hand. Unlike rats and pigeons, you don’t have to house, feed, or raise them. You don’t even have to go find them. If you are a professor at a research university, they sign up for your classes; they actually pay you! This explains why so many psych research papers use undergrads; or at least they did, until paying people to take online surveys became even easier. Perhaps convenience eats all worldviews

The transitions from introspection to behaviorism to cognitive psychology are good examples of what it looks like to change scope. But I don’t think any of these were successful revolutions, because none of them gave psychology a real paradigm (though behaviorism came surprisingly close).

These kinds of border skirmishes are common enough. The study of heat and light used to be considered a part of chemistry; now they’re both squarely inside physics. But real revolutions tend to be much more upsetting. So maybe these revolutions in psychology weren’t successful because they didn’t change the scope enough.

Kuhn usually acts as though every revolution involves just one science that has clear boundaries. A crisis comes along, and you swap out the old paradigm for a new one — but you have one paradigm before the revolution, and one paradigm afterwards, and the boundaries don’t change much. This does describe a few cases, like the Copernican Revolution. But the reality wasn’t usually so simple.

When science was just getting started, people seemed to expect that it would stay united in one big happy field, which they called natural philosophy. But they were wrong. Science ended up splitting up into a bunch of different fields. Within a couple of generations they had already specialized into physics, chemistry, biology, and various others. Today, even sub-disciplines like organic vs. inorganic chemistry arguably have different paradigms.

This didn’t seem very painful. My impression is that people trying to figure out natural philosophy came up with a bunch of different directions, people signed on to whichever one they liked best, and 100 years later people discovered they were in different fields. They diverged, but it was pretty quiet and amicable. Not much of a revolution!

More famous is the exact opposite.

Newton’s physics combined mechanics (“the area of physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects”) with astronomy. This seems unremarkable to us, but it’s hard to express just how surprising it was at the time.

Nothing could be so obvious as that the Earth and the heavens are subject to separate laws. The heavens are perfect and eternal, while the Earth is changing and impermanent. The laws that govern Earth are the laws of gross bodies (which change, decay, and rot), while the laws that govern the motion of the spheres are divine (the spheres are probably pushed around by angels or something).

But in Newton’s paradigm, mechanics and astronomy were governed by the exact same set of laws. Worse, instead of being formed of pure celestial fire, the stars were made of the same kind of crude material substance as the Earth. And worse still, Newton’s theory of gravity said that not only did the stars and planets exert an influence over the Earth (acceptable), but the Earth itself had an influence over the stars and planets (unacceptable), in fact the exact same kind of influence in the same measure (practically blasphemy). But Newton’s paradigm was so useful that eventually there was no sense in seeing things any other way.

Other examples are out there if you look. Something similar happened when James Clerk Maxwell unified electricity, magnetism and light. We thought these were three largely different things, and physics changed when Maxwell showed they could all be described by the same laws.

If psychology doesn’t have a full scientific paradigm right now, then the next paradigm won’t come from a real scientific revolution, because revolutions only happen when a mature science switches between one complete paradigm and another. This does limit how much we can learn by looking at stories from other revolutions.

But as the examples from revolving in and out of behaviorism show, we should expect that any serious attempt at building a paradigm will involve some kind of change in scope.

We may not be able to predict the next paradigm. But if we assume that the next paradigm, whatever it might be, will mean some kind of change in scope, we can look for our next paradigm by thinking about what kinds of changes in scope seem possible. We can consider how we might shift our boundaries, what divisions we can ignore, what new distinctions we can adopt, what neighboring fields we might be absorbed by, and even what fields we might be able to absorb.

If psychology’s first paradigm does come from a major revolution, there’s a good chance it will involve the field splitting up, or different fields coming together. “Psychology” as a field may not survive any more than Alchemy or Natural Philosophy did. But it wouldn’t be wrong if we tear down our walls and use the stones to build something better, and we shouldn’t be afraid of the possibility that the resulting science might have a new name or new boundaries.

And the Paradigm is….

In a moment I’m going to show you a list of some possible paradigms, directions that might be a hint at the future of psychology.

This particular list is based on discussions I had with students in CS-0257 Psychological Revolutions, a class I taught at Hampshire College in Fall 2023. So before diving into the list, I want to give special thanks to my students for their part in coming up with these ideas.

This list isn’t the only list of possible futures. I won’t even claim this is my list per se. But after a semester of conversation, these are the ideas that had the best showing, and I figured an artifact like that should be preserved for posterity.

Psychology + Neuroscience

Uniting psychology and neuroscience is a very popular idea. Laypeople often assume that psychology and neuroscience are already one field, and are surprised to hear they’re not.

But to psychologists, combining the two fields would be revolutionary. The very suggestion challenges a core assumption about implementation, or the details of how the brain is wired up. You might think that the wiring is very important, but behaviorism and cognitive psychology both agree that implementation doesn’t matter, and they’re very explicit in this belief.

Behaviorists were interested in the physical structures of the body. But they saw the nervous system as not special in any way, no more deserving of their study than any other part of anatomy. John Watson, who wrote the book Behaviorism and kind of founded the field, said:

Should We as Behaviorists Be Especially Interested in the Central Nervous System? Because he places emphasis on the facts of adjustment of the whole organism rather than upon the working of parts of the body, the behaviorist is often accused of not making a place in his scheme for the nervous system. … Many of our so-called physiological psychologies are filled with pretty pictures of brain and spinal cord schemes. As a matter of fact we do not yet know enough about the functioning of brain and spinal cord to draw diagram about their functions. For the behaviorist the nervous system is, 1st, a part of the body—no more mysterious than muscles and glands; 2nd, it is a specialized body mechanism that enables its possessor to react more quickly and in a more integrated way with muscles or glands when acted upon by a given stimulus than would be the case if no nervous system were present.

Elsewhere in the same book, Watson gives this example:

Responses may be wholly confined to the muscular and glandular systems inside the body. A child or hungry adult may be standing stock still in front of a window filled with pastry. Your first exclamation may be “he isn’t doing anything” or “he is just looking at the pastry.” An instrument would show that his salivary glands are pouring out secretions, that his stomach is rhythmically contracting and expanding, and that marked changes in blood pressure are taking place—that the endocrine glands are pouring substances into the blood.

Watson was a bit unusual, even for a behaviorist, and some of his positions were extreme. But this position survived into mainstream behaviorism. B. F. Skinner expressed the same idea, sometimes even more bluntly, like when he said:

In regarding behavior as a scientific datum in its own right and in proceeding to examine it in accordance with established scientific practices, one naturally does not expect to encounter neurones, synapses, or any other aspect of the internal economy of the organism. Entities of that sort lie outside the field of behavior as here defined.

Or when he said:

Cognitive psychologists like to say that “the mind is what the brain does,” but surely the rest of the body plays a part. The mind is what the body does. It is what the person does. In other words, it is behavior.

Behaviorism kind of goes back and forth between saying neurons are outside of psychology, and saying that neurons are included, but only a small part of a whole-body approach. But the idea that behavior can be reduced to the actions of neurons alone is absolutely rejected.

However, I think Skinner is misrepresenting the cognitive psychologists in that last quote, because they don’t care much about the brain either. Yes, these days they will gladly stick undergrads in an fMRI machine so they can put “brain scans” in their papers; this makes it easier to win grants and get published in fancier journals. But they don’t include these as a core part of their science — scanning brains is only useful insofar as it helps you get closer to mental states (and win grants and publish papers). The actual brain is no more interesting to them than the details of the ear, skin, or eye. As I heard one psychology professor say, “I don’t know my axons from my dendrites.”

If you go back to the foundations of the field, you can see that cognitive psychology doesn’t encompass neuroscience either, and that this exclusion is a real commitment. In the book Cognitive Psychology, Ulric Neisser wrote:

Psychology is not just something “to do until the biochemist comes” (as I have recently heard psychiatry described); … [the psychologist] will not care much whether his particular computer stores information in magnetic cores or in thin films; he wants to understand the program, not the “hardware.” … Psychology, like economics, is a science concerned with the interdependence among certain events rather than with their physical nature. … We must be careful not to confuse the program with the computer that it controls. Any single general-purpose computer can be “loaded” with an essentially infinite number of different programs. On the other hand, most programs can be run, with minor modifications, on many physically different kinds of computers.

Many people are surprised to learn that there’s some real math behind this idea. The Church–Turing thesis is the name for the idea that there’s only one kind of computation: If you can run some program on one computer, you can run it on any other kind of computer, and it doesn’t matter if that computer is made of gears, levers, hydraulics, silicon — or yes, neurons.

This is where you get all those silly stories about how you can build computers using swarms of crabs, or how you can build a computer that can play Minecraft inside Minecraft. As long as it’s Turing-complete, you can run anything on anything (though if your computer is composed of swarms of crabs, it will be slower and buggier than other computers).

This thesis hasn’t been strictly proven in the way mathematicians usually like, but we’ve never found a program that can run on one kind of computer but not on another, or a kind of computer that can work through algorithms that other kinds of computer can’t figure. It would be an enormously big deal to discover some kind of incompatible program, or totally original kind of computer. But we have never discovered such a thing, and there aren’t any leads.

(To the best of my understanding, quantum computers are not a different kind of computation — they’re able to do some things much faster than classical computers, but mostly in the same way that your silicon computer is much faster than a computer made up of swarms of crabs.)

I’m not sure what to think of the idea that neurons don’t matter. On the one hand, even though most people find it unintuitive, treating implementation like it doesn’t matter is a core commitment of both behaviorism and cognitive psychology. And it has pretty solid support from information theory and what we understand about computation. Whatever algorithms might govern the mind, you should be able to run the same algorithms on a PS4, they will just take slightly longer.

On the other hand, any major assumption shared by both behaviorism and cognitive psychology is exactly the kind of assumption that might be holding us back! Any shared assumption is likely to be shared because it is a blind spot. Maybe this is one of those sacred mysteries — their commitments disagree with common sense only because if they didn’t have something counterintuitive to say, laypeople wouldn’t feel the need to listen to them at all.

I also think it’s possible to take the information theory arguments too seriously. It’s true that (as far as we know), any algorithm can be run on any computer, regardless of physical substrate. But that doesn’t mean that all physical systems compute identically. Computers made out of silicon are much smaller and run much faster than computers made out of brass gears, which is why you’re reading this on a silicon computer and not a brass one. The fact that the brain is made of neurons probably can tell us something about the mind; though it’s not clear how much it can tell us, or how important that information might be.

What would it even mean for neuroscience to subsume psychology? I think it would be too nitty-gritty. Doing psychology as neuroscience seems like trying to describe the subway system without being able to talk about trains, stations, or riders — instead you can only talk about atoms and molecules. Trains, stations, and riders are all made up of molecules, but this seems like the wrong level of analysis.

My intuition is that the marriage of psychology and neuroscience simply isn’t weird enough. Newton didn’t invent his paradigm by switching to a more common-sense perspective on physics. He got there by putting together pieces no one else expected to go together, and ending up with a result no one imagined, a result that almost everyone found shocking and offensive. I don’t think psychology will drop such a bombshell, but I do think whatever happens will be pretty strange.

Psychology + Economics

Psychology and economics are both fields about people — their thoughts, their behavior, and how they decide what to eat for lunch.

The main reason to suspect these could become the same field is that when people have tried to combine the fields in the past, it’s gone pretty well. There’s no Nobel Prize in psychology, but when psychologists win Nobel Prizes, they win them in economics; one in 2002 and (arguably) one in 2017. Some of the studies that came from this collaboration are among the most famous and robust in psychology; that shows a lot of promise. Psychologists don’t win Nobel Prizes in medicine or chemistry, or at least we haven’t yet.

However, the main reason to suspect these won’t become the same field is… all that promising work. The research that won those Nobel Prizes was mostly conducted in the 1970s, and arguably that was when the relationship peaked. If a union between psychology and economics were going to happen, you’d think that after 50 years of effort, we would have seen more progress. At some point you have to accept that the relationship is over, and move on.

There's good reason to think that the union of economics and psychology was a weekend fling rather than a marriage: the entire relationship hinged on the falsification of the Rational Actor Hypothesis. That was the one thing they had in common, nice while it lasted, but now they're running out of things to talk about.

But this isn’t a knock-down argument. Economics doesn’t have a paradigm either, and the overlap is hard to ignore. Perhaps we’re just smushing together psychology and economics in the wrong way. If we smush together different parts of the fields, maybe that will prove a more successful smushing.

Psychology + Medicine

An underrated fact about psychology is that the brain is an organ like the kidneys, lungs, and spleen.

Some people will say that while it’s true the brain is an organ, it is a much more important organ than the spleen. To these people I say:

As a hypothesis, “there’s a set of laws that governs all biological organs” sounds decently plausible. Whatever these laws are, they’ll govern the brain as much as they govern the spleen. If the laws are trivial, like “organs are wet and inside the body”, that won’t make for much of a paradigm. But if there are profound similarities between all the organs, that begins to sound like a real science.

The main problem here is that medicine doesn’t have a paradigm of its own, so we can’t freeride on their hard work. You’d have to invent a new paradigm that includes some kind of commitments about the function of organs, and gives constraints that apply equally to the brain and the kidneys.

I’d find this outcome kind of amusing, because it reminds me so much of behaviorism’s whole-body approach to psychology. That commitment was abandoned when behaviorism fell, but strictly speaking it’s not incompatible with cognitive psychology. The mind can be a computer whether all of that computation happens in the brain or elsewhere. So even though I think behaviorism was wrong, this gives the possible union with medicine a little more promise, because we know the idea used to be popular and there was no obvious reason to abandon it.

Psychology of Plants

Under behaviorism, psychologists spent a lot of time studying non-human animals. When behaviorism fell, animals were mostly dropped. These days, almost no psychologists study animals.

One change we can tinker with is making this circle of research subjects smaller or wider. It’s hard to see how you could make the circle smaller. Psychologists these days claim to study humans, but they mostly study adults. Actually, mostly just adults in their 20s. Actually, mostly college-aged psychology majors studying at American research universities.

So it seems more promising to think about how we could make the circle wider. We could expand it back to the scope of the behaviorists, and include all animals. Or we could expand it even further.

Everyone knows that Venus flytraps snap shut their jaws on their prey, and that daisies turn to follow the sun. Isn’t that behavior? You can point out that a Venus flytrap only closes its jaws when something touches its trigger hairs. But I don’t see how this is meaningfully different from a statement like, “my dog only bites me when I poke it in the eye”. There’s a motor action that occurs in response to a stimulus, and something happens in between. Go to the Wikipedia article on plant arithmetic, thou sluggard. Consider her ways and be wise.

While these behaviors are definitely simple, to my mind this is so clearly behavior that no other examples are needed. But in fact we do have more complicated examples of plant behavior.

Take the Boquila, a flowering vine that grows on a host tree and imitates the host’s leaves, including the size, shape, and color. They can mimic over 20 species of plants, and don’t need to touch the host trees to mimic their leaves. They’ll attempt to mimic the leaves of their host even when that host is a fake plant made out of plastic. Some people have looked at these facts and concluded that this is evidence for plant vision.

Even the humble pea plant (Pisum sativum) may be able to sense the size of a stick before touching it. Peas are climbing vines — as they grow, they reach out and grab on to surrounding objects for support. This spinning search (circumnutation) is too slow to see under normal circumstances but is perfectly visible in timelapse. And the findings of that one paper, at least, suggest that plants spin faster when they are trying to grab a thin stick than when they are trying to grab a thick one. This could be more evidence of plant vision, but the authors think it might actually be evidence for plant echolocation.

It’s easy to oversell these results. A lot of people miss the message and go straight for “are plants intelligent?”2 I think the answer, based on these behaviors at least, is obviously no. These plants are not translating Ovid; they probably couldn’t even catch a fly ball. But to the question “do plants think?”, the answer is obviously yes. Clearly some kind of computation is happening here. The plant is sensing something about the world, it makes some kind of internal comparison(s), and this affects its behavior. That’s thinking in my book.

These examples could also be better documented. It’s possible that some of these claims may not hold up. But that’s the point: plant behavior should be better documented. And plant behavior is the domain of plant psychologists

To my mind, the question isn’t whether we decide to expand the scope of psychology to plants. The question is whether there’s any prospect at all of keeping plants out! They may not be as quick as animals, their cognition may not look all that much like ours, there may not be anything happening “upstairs”, but there is clearly some kind of computation happening somewhere.

I don’t think this is enough to tell us what psychology’s first paradigm will be. But I do think that whatever the eventual paradigm of psychology is, it will have to include plants. So any idea for a paradigm that would exclude plants is on shaky footing. And any idea that clearly includes plant psychology is all the more promising for that inclusion.

If you take the other side of that wager, psychology won’t include plants, that still gives you an interesting starting point. Try to imagine what paradigm could possibly exclude plants. Behaviorists and cognitive psychologists have mostly ignored plants, but that was an oversight — these paradigms don’t rule out plants, psychologists just didn’t think of it. I think you’ll find that it’s surprisingly hard to draw the lines in a way that leaves plants on the outside while keeping all the normal parts of psychology in.

In any case, a few notes about the practical implications:

It’s hard to recruit human participants for anything other than surveys, and hard to house a colony of five hundred rats, but relatively easy to grow your own research subjects when they are tomatoes. That means plant psychology is good for replication. A packet of snow peas is cheap. You can run studies on plant vision or plant echolocation in the comfort of your own back garden.

One reason people choose to do research with animals is that you can do things to animals that you can’t do with humans, like keep them in cages for their whole lives, or cut apart their brains and see what happens. By similar logic, with plants you can run studies that you could never ethically or practically run on animals. You can do things to plants that you would never consider doing to an animal, and grow them in any situation you need, with no danger to your conscience. At least, that is, until we figure out whether or not plants can feel pain.

Psychology of Memory

In a computer, each file is stored in a specific file format, a set of rules that govern how the data inside the file is organized. This is where we get JPEG, WAV, PNG, PDF, TXT, and GIF. All of these are different formats for storing different kinds of information.

Most file formats include some kind of compression so they can hold the same information (or a good approximation of the same information) using less storage. This compression is sometimes characteristic: you can tell the file format by noticing signs of the compression. You can recognize a JPEG by the characteristic chunky compression, like so:

It’s a little subtle in this example, because the compression isn’t that extreme. But if you look closely you’ll see lots of little square regions in the image, some of them with strange wave patterns. These are “JPEG artifacts”, a flaw that reveals the nature of the compression technique.

You can find a description of the techniques behind JPEG here, and you can play with the algorithm using a tool by DefenderofBasic that’s hosted here. But I’m going to skip over most of the details, we’re not here to talk about JPEGs. We’re here to talk about how file formats sometimes show their fingerprints on the data. In this case, JPEG compression starts by breaking the image into 8×8 pixel squares, and if you check a JPEG, any artifacts should be in chunks of 8x8 pixels.

In the brain, memories are stored as…??? Honestly, who knows. In my opinion, this is one of psychology’s major blindspots.

I think the answer I’m supposed to give is “memories are stored as associations”. But this doesn’t hold up to closer scrutiny. First of all, associations between what and what? If “the Eiffel Tower” is associated with “Paris”, what does the association represent? Does that mean the Eiffel Tower is in Paris, or that Paris is in the Eiffel Tower? Association by itself is too simple to represent even the most basic information.

You can argue that we store memories in the kind of associations used in Large Language Models (LLMs). But LLMs actually make very characteristic errors, like not being able to count the number of R’s in the word “strawberry”, which comes from the fact that their inputs are tokenized. This is characteristic of LLMs just like how 8x8 square artifacts are characteristic of JPEGs, and if humans stored our memories the same way, we would make similar errors.

If you read an intro psych textbook, you will see something like: memory consists of encoding, storage, and retrieval. But this is true of any sort of storage. Index cards are also encoded (on paper, in the English language, using approximations of Roman characters written in pen), stored (in little boxes to keep them from getting wet or getting eaten by insects, which would damage their information), and retrieved (using the labels written on the boxes).

The landmark studies in memory are mostly on a single theme, they mostly demonstrate different ways that memory is not perfect. While overturning common misconceptions is an important job, and one we’re reasonably good at, this is short of the abilities of a mature science. Some hints about memory come from studies that show that people can remember more things, or remember them better, when they use certain techniques or are in certain situations. But I’ve never encountered a study that uses this to argue for or against a particular kind of encoding.

The very best evidence about the nature of memory comes from people with severe brain damage — most famously, HM. HM could hold on to new information for a couple of minutes, but soon forgot, and couldn’t make any new long-term memories. Cases like this make it pretty clear that there are at least two kinds of memory, which we sometimes call short-term and long-term. That’s important, but it’s a lot like saying a computer contains two kinds of file types. It doesn’t actually tell us how those file types work.

This is a tough nut to crack, but if someone did start getting close to a theory of the file format(s) of memory, there’s a good chance it would give us our first paradigm. Memory isn’t everything, but it’s pretty central. We make decisions in the light of our previous experiences. We perceive things in the context of things we’ve seen before. Everything is shaped by memory; maybe that’s where we should hang our hat.

We might be able to get there by looking at plants. Plants seem to form memories, but they don't have brains or even neurons, so how are they storing that information? Because it’s easier to do invasive research on living plants than on living animals, we might be able to look inside living plants and actually see the memories being formed.

But there are other angles too. One of the most surprising passages in the book Cognitive Psychology is one where Neisser shares a theory of memory that has certainly fallen out of the mainstream, but for all I know, may still be plausible. He says:

No one would dispute that human beings store a great deal of information about their past experiences, and it seems obvious that this information must be physically embodied somewhere in the brain. Recent discoveries in biochemistry have opened up a promising possibility. Some experimental findings have hinted that the complex molecules of DNA and RNA, known to be involved in the transmission of inherited traits, may be the substrate of memory as well. Although the supporting evidence so far is shaky, this hypothesis has already gained many adherents.

Psychology of Value

Behaviorism and cognitive psychology are more similar than they would like to admit. While the cognitive revolution stressed their differences, they share a lot of commitments.

For one, the two schools share a similar concept of value. Both schools think that value is an important part of psychology, that value itself runs the gamut from reward to punishment, and that behavior is driven by some kind of function that aims to increase reward and decrease punishment. Sometimes they call this the “hedonic principle”.

Because it’s so central, and has gone unquestioned for so long, I think a new paradigm might come out of a new way of thinking about value. A similar possibility would be a new paradigm that gives value a different kind of role in psychology, where it’s less central, or performs a different function.

I’ll give just one example of why I think this could be the right direction. There’s a 2015 paper from a team of psychologists led by Tim Wilson which found that if you ask people to sit in a room for 15 minutes, with a button they can press to receive a painful electric shock (they had already experienced the shock in an earlier stage of the study, so they know it’s painful), 25% of women and 67% of men will give themselves at least one shock before the 15 minutes is up. One woman shocked herself nine times, but the real outlier is the man who gave himself 190 shocks, slightly more than one shock every five seconds.

The authors kind of go back and forth on how to interpret this. Usually they stick to the standard cognitive psychology model of value: a shock is always a punishment, so if people chose to shock themselves, they must have been doing it to avoid some greater punishment. In the abstract they write that many people “[prefer] to administer electric shocks to themselves instead of being left alone with their thoughts”.

They also interpret the main finding as “what is striking is that simply being alone with their own thoughts for 15 min was apparently so aversive that it drove many participants to self-administer an electric shock that they had earlier said they would pay to avoid”, and they go to some lengths to show that people don’t enjoy being alone with their thoughts.

But other times they admit that being alone with your thoughts (BAWYT) doesn’t seem like it could be all that bad. At one point they write, “many participants elected to receive negative stimulation over no stimulation”, suggesting that the value of BAWYT is zero rather than negative. And their attempts to show that BAWYT is agonizing fall pretty flat. They say that “participants did not enjoy the experience very much”, but across six studies, the average rating for BAWYT was 5.12 on a 9-point scale. This is the definition of middling, and doesn’t suggest it was all that negative.

Why did that one guy shock himself so many times? You can cling to the standard way of thinking about value, and say that sitting quietly must have been worse than the shocks. Or you can see this as evidence that the old way of thinking about things is wrong, and that we need to find a new model for value, a model where shocking yourself 190 times in a row makes perfect sense. Because to at least one participant, it does.

Psychology Splits

I said a bit about this before, but I want to say it again at the close: One of the biggest assumptions is that when this all shakes out, there will be just one field that is still called “psychology”.

But it may not go that way. In the next revolution, psychology may split up. Psychology might even split three or four ways. We shouldn’t try to squeeze everything in one jacket if the jacket doesn’t fit.

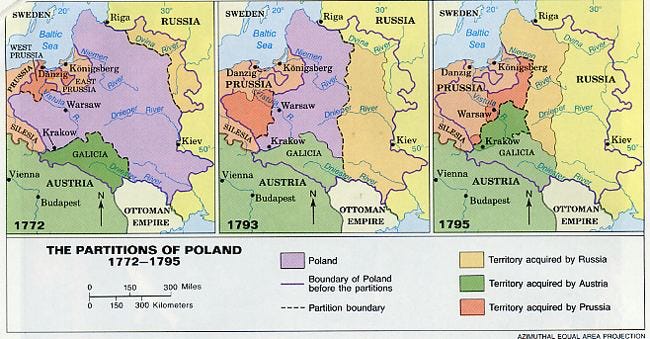

The study of the human mind is already divided between different fields. Many parts are given to economics, sociology, neuroscience, medicine, and so on. Maybe these divisions will just get more and more useful. Psychology might even go the way of Poland in 1795 and cease to exist as a sovereign field, its territory divided up between its more powerful neighbors.

Personally, I think this is unlikely. Many fields would like to conquer psychology; but none have succeeded. I think there’s a unique field or two in here somewhere.

But that’s the thing, there might be more than one. There are many divisions within psychology, like decision-making, sensation, and emotion. Maybe these sub-areas will prove the most productive, and will split the field from within. Maybe memory and perception end up together in one new field, while personality and motivation end up in another.

Psychology might also divide in more complicated ways, maybe based on some of the ideas above. For example, memory might form a new field with neuroscience (since the storage of memories might be closely connected to how neurons work), that is neither traditional psychology nor traditional neuroscience, but some kind of new field based on the study of particular methods of storing information. Meanwhile, motivation might form a new field with medicine, as the functions of the brain and other organs are found to go hand in hand with the reasons why we find it easy to drink sugar water, and hard to pretend to pay attention during the quarterly staff meeting.

The only thing we should expect for sure is this: when the revolution comes, it will be surprising. And, you know what? I think it will also be delightful.

It’s silly to think there are only eight planets in our solar system. It’s equally silly to think there are nine. Clearly there are hundreds. Recommended reading are these Metzger pieces: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1805.04115 ; https://arxiv.org/pdf/2110.15285

Some great examples at that link, though the Milgram comparison is extremely half-baked.

This is a big deal, thanks for writing about it so thoroughly. You and your readers would likely appreciate Roger's Bacon's post from yesterday, Epistemic Hell (https://www.theseedsofscience.pub/p/epistemic-hell). Both of you are zooming in on the void at the heart of the field, the absence of a clear paradigm with clearly-defined entities, relationships and contexts that can guide engagement.

In Kuhn's words, "In the absence of a paradigm or some candidate for paradigm, all of the facts that could possibly pertain to the development of a given science are likely to seem equally relevant. As a result, early fact-gathering is a far more nearly random activity than the one that subsequent scientific development makes familiar. Furthermore, in the absence of a reason for seeking some particular form of more recondite information, early fact-gathering is usually restricted to the wealth of data that lie ready to hand."

For me, this speaks to the strong need to look for data outside what lies "ready to hand." And especially, the place to look for that data, I believe, is at the heart of the matter: right in the thick of subjective experience itself. How can we observe subjective experience in a way that enables us to bridge the subjectivity barrier and come away with data that can reliably reveal patterns upon skillful analysis? (I don't think surveys are the way to go.)

I've been working on this for quite some time, and will be ready in a few weeks to release the first volume presenting an innovative methodology that provides the beginning for such disciplined, scientific observation of subjective experience. I won't say more about it here -- I'm laying it out gradually in my 'stack. But I will say that it does point to a significant possibility for a new paradigm in the form of a field dimension of conscious experience.

Keep doing what you're doing, Ethan. I appreciate your essays!

So many paradigms are based on metaphors. Metaphors are not physical models but literary devices that replace a complex domain (psychology/brains) with a familiar domain (computer science/computers). It hides more differences between the two domains than it reveals similarities. The human brain is so complex and so unique in the world that any single model or metaphor will ultimately fail. For a review of metaphors used to describe cognition, see https://tomrearick.substack.com/p/metaphors-we-think-by.