Alchemy is ok

A response to Paul Bloom's response to Adam Mastroianni

[Thanks to Paul for insightful comments on an early draft of this post.]

I HAVE BEEN in the middle of composing a pamphlet making a Summary of Alchymy’s Greatest Hits and my recent broadside addressed to the publick (the cause of some Complaints), expressed no Doubts to the strength of our Art, but was a meer measure to see whether there were any Discovery or Phænomena I had miss’d. Indeed I profess and doubt not that Alchymy has right to several major recent Discoveries, and these same Discoveries I did Bear in Mind at the time of my asking.

Perchance you hold suspicion that I am no honest Philosopher but instead a base Mountebank, so if You will give me leave, I shall Briefly propose to you a list of ten (seek my treatise Chymie (soon out in octavo!) for more details on each). All of these are robust findings, discovered (or at least substantially built upon) by Alchymists in the last Centuries, and I hold that most of them are interesting to divers Modern Naturalists, Physitians, and Philosophers.

Gold is a Body so fix’d, and wherein the Elementary Ingredients (if it have any) are so firmly united to each other, that we finde when Gold is expos’d to the Fire, how violent soever, it does not discernably lose any of its fixednesse or weight, so far is it from being dissipated into those Principles.

However, the same Gold will also by common Aqua Regis, and (I speak it knowingly) by divers other Menstruums be reduc’d into a seeming Liquor, in so much that the Corpuscles of Gold will, with those of the Menstruum, pass through Cap-Paper, and with them also coagulate into a Crystalline Salt.

On sealing up a Mouse and a Candle lit a-Flame in a close Glass-Vessel, and watching to see what happens, the Mouse invariably dies before the Candle.

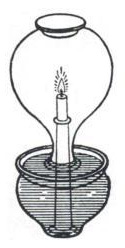

On inverting a Glass-Vessel over the Flame of a Candle and surrounding the Vessel's neck with Water, first the Water rises some height into the Neck of the Vessel, then after some time the Candle dies. For it seems very considerable, that parts of the Air in the Vessel are converted to Fire, and the little nimble Atoms of Fire escape through the Pores of the Glass.

After an eruption of Vesuvius, the inclination of a Magnetic Needle in the same Town made a considerable Swing.

You may Wonder that a red-hot piece of Iron is attracted (as they speak) by a Magnet, though the Magnet shows no attraction for the Iron.

Impure Silver and Lead being expos’d together to a moderate Fire, will thereby be colliquated into one Mass, and mingle; whereas a much vehementer Fire will drive or carry off the baser Metals (I mean the Lead, and the Copper or other Alloy) from the Silver, though not, for ought appears, separate them from one another.

Nothing could seem so simple as the Burning of Wood, which the Fire Dissipates into Smoake and Ashes. But both may afterwards be Separated by other Degrees of Fire, whose orderly Gradation allowes the Disparity of their Volatileness to Discover it self. The latter of these is Confessedly made up of two such Differing Bodies as Earth and Salt; and the Former being condens’d into that Soot which adheres to our Chimneys, Discovers it self to Contain both Salt and Oyl, and Spirit and Earth (and some Portion of Phlegme too).

Oil of Vitriol, upon a rough Bladder-Stone in a Glass or Earthen Vessel, remains and acts as a Menstruum.

The Dutch-Men that were forc’d to Winter in that Icie Region neer the Artick Circle, call’d Nova Zembla, relate that there was a Separation of Parts made in their frozen Beer about the middle of November, but of their Sack, which was later Frozen very hard, yet was not divided by the Frost into differing Substances, after such manner as their Beer had been. Thus even Cold sometimes may Congregare Homogenea, & Heterogenea Segregare.

I’m not actually a 17th-century alchemist working on a pamphlet — I composed this in response to fellow-psychologist Paul Bloom, who marshaled a list of ten “major recent discoveries” in psychology in support of the argument that psychology is ok (itself a response to an argument by my friend Adam). I think his list looks a lot like mine, though the prose is slightly more modern.

All of the alchemical findings above are paraphrased examples from real alchemists or early chemists. In several cases I have cribbed directly from Robert Boyle’s explanations of discoveries made around or before his time.

To the best of my limited chemical knowledge, all of the findings on this list ended up being both true and important. And the list is more than just a collection of scattered one-off findings, it shows some real direction. For example, items 3 and 4 are clear forerunners to the eventual understanding of combustion and oxygen. Items 1, 2, 7, and 8 all touch on questions of what elements exist (e.g. is gold an element or is it made up of other elements) and how they can be distinguished and studied. My list excludes alchemical bloopers like “the magnet briskly rubbed with garlic or placed near a diamond loses its force, which, however, can be fully restored if boar’s blood is poured on to the magnet”. Only the good stuff.

The truth of the matter is that for hundreds of years alchemy did produce major discoveries, reliable and robust findings, and many of these findings later turned out to be very important. (They also produced lots of crap, but that doesn’t matter, because science is a strong-link problem and over time the cream floated to the top.) We shouldn’t dismiss the alchemists.

But are we to conclude from this list that “Alchemy is ok”? I don’t think so. At no point was alchemy ever ok. There was no agreement on basics like 1) are bodies made of elements, or elements and principles, or “Materiall Ingredients”, or something else, 2) assuming there are elements and/or principles or something else, what and how many are there, 3) how do you figure out whether or not something is an element or principle, or if it is a mixed body, 4) do you have to conduct division of bodies by fire alone or are there other methods of studying mixed bodies, and 5) what else do you need to measure to make sure your alchemy is replicable, viz. things like position of the sun and moon and planets within the zodiac, direction and speed of the wind, and temperature (which was still not very well understood). They needed Boyle, Lavoisier, Dalton, and a host of others to give them shape and turn them into chemistry. In Kuhn’s terms, they needed a paradigm.

"Paradigm shift" is now so widely used that it has lost much of its force. People think paradigm shifts work along the lines of, "chemists used to wear periwigs and now they don't." But Kuhn meant something much more than just changes in fashion. He meant changes in basic concepts, and beliefs about “the fundamental entities of which the universe is composed” (his words). If you asked Galen of Pergamon which of the four humors you’re deficient in, he would gladly tell you. If you asked a modern doctor the same, they literally won't know how to answer. “I need more phlegm, how do I get more phlegm?” no longer means anything in medicine, and forget about asking for black bile.1

This is why paradigms don't spontaneously generate from big stacks of findings. You need a revolution, and often you can’t make full sense of your most important discoveries until you have one. Boyle knew it was important that gold never lost weight no matter how much you heat it up, but he didn’t know why it was important. That's why a "psychology is ok" attitude is self-defeating: if we keep doing what we're doing, we'll only get more of what we already have.

Psychology today is about where alchemy was in the year 1661. Like the alchemists, we do sometimes produce true and important findings, but we have no way of making sense of them or fitting them together. We need a paradigm to give us shape and turn us into a mature science. No number of discoveries, however robust or interesting to non-specialists, can make that happen.

It was important to notice that a candle under a glass draws water up into the vessel, then dims and goes out. This was an early clue about the nature of combustion, and a sign of the element that would come to be known as oxygen. The effect is so robust that you can easily try it at home. But Philo of Byzantium was no chemist — he looked at this and saw atoms of fire escaping through pores in the glass! You can run experiments like this for hundreds of years without ever really understanding what's going on.

As Bloom points out, we know that all sorts of psychological traits (or at least measures we conceive of as related to those traits) are heritable, that people overestimate the frequency of rare but conspicuous events, and that some fears are shared across all humans. But how these facts fit together remains an open question. When we figure out the psychological equivalent of discovering the elements, we'll have more than just a collection. We'll have a paradigm.2

How do we do that? Good question, and a hard one, but I hope to write more about it soon. In the meantime, you can always go back and try to figure out how people like Newton, or Lavoisier, or Darwin did it. We have something very useful that none of those guys did: their example. What they wrote is in the public domain — you can read it, and sometimes you can practically see the gears turning. The more history of science you have, the more you can understand how it works, and how to make it better. But first you have to read it.

Paradigm shifts really do make the previous regime nonsensical. For example, look at Boyle on the humors:

Mans Bloud it self as Spirituous, and as Elaborate a Liquor as ’tis reputed, does so abound in Phlegm, that, the other Day, Distilling some of it on purpose to try the Experiment (as I had formerly done in Deers Bloud) out of about seven Ounces and a half of pure Bloud we drew neere six Ounces of Phlegm, before any of the more operative Principles began to arise, and Invite us to change the Receiver. And to satisfie my self that some of these Animall Phlegms were void enough of Spirit to deserve that Name, I would not content my self to taste them only, but fruitlesly pour’d on them acid Liquors, to try if they contain’d any Volatile Salt or Spirit, which (had there been any there) would probably have discover’d it self by making an Ebullition with the affused Liquor.

Or quite possibly, more than one.

Great post! It does feel like psychology today is about where alchemy was in the year 1661, and in the case of my own profession, psychiatry seems to be where medicine was prior to germ theory of disease.

PS. You might be interested in this conversation I had with the neuroscientist Nicole Rust https://awaisaftab.substack.com/p/advancing-neuroscientific-understanding

She brings up Ptolemy at one point: "My impression is that we haven’t figured out the right ways to think about many problems in brain/mind research. Rather, it often seems like we are working in frameworks akin to Ptolomy’s wonky descriptions of planetary motion (under the misguided assumption that the planets revolve around the earth)."

And my response was: "My understanding is that Ptolemy’s model was fairly successful in accounting for planetary positions (and predicting things like solar and lunar eclipses) and enjoyed near universal support among scholars until it was displaced. It is difficult to think of anything comparable in the brain-behavior sciences. There is no unifying model of brain-behavior relationship that is empirically successful and is supported by scientific consensus. Different approaches to research are often dominant at different times, but that dominance is not typically because of compelling evidence; it is usually driven by the shortcomings of the previously dominant approach and by the enthusiasm that this or that new approach will deliver will the answers."

And the goal of kicking psychology out of its current state of alchemyhood is definitely a more dire task considering how today so many ideological voices and persuasions have taken the field hostage, not only making free enquiry difficult but their expression even more prohibitive. As I once quipped, the field of psychology is still largely a Freudian world, and we're still very far from our own Copernican revolution.