Why Science Should Learn to Love Metaphysics

AKA Why I am a Metaphysician

This is the script for a talk that I gave at Reinventing Science, the recent mini-conference that I co-organized.

In the Beginning

In the beginning, science was all about metaphysics. A huge number of our questions were metaphysical. How do time and space work? What is stuff made of? How many different kinds of plants and animals are there? Is heat the absence of cold, or is cold the absence of heat, or are they two different fluids? That kind of thing.

The scientific revolution came out of these projects. Descartes convinced most physical scientists that the material universe is made up of microscopic corpuscles, and that all natural phenomena can be explained in terms of the shape, size, motion, and interaction of these tiny snooker balls. Newton and Flamsteed and others took these metaphysical ideas and started framing out modern physics.

You saw the list of elements go from four entries to ???, uhh, actually we’re still figuring that out, get back to you in 100 years. There might be a couple different kinds of air, but we’re pretty sure that the list of elements includes fire and light.

Copernicus did the same thing to astronomy. The Earth, which used to be the center of the universe, became a planet. The sun, which had been a planet, became a star. The moon, which had also been a planet, was enough of a problem that we needed to invent an entirely new kind of thing for it to be, a satellite.

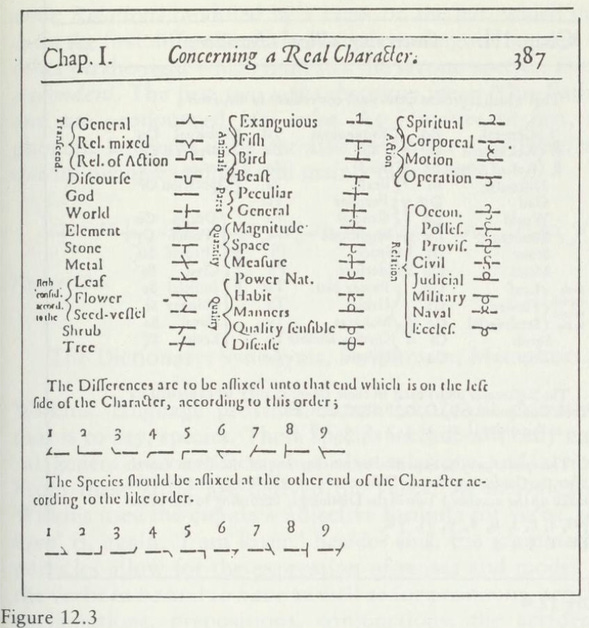

Some of these projects had better results than others. John Wilkins spent his time inventing a Philosophical Language, which he planned would be a system for classifying every possible thing and notion in the entire universe. In his system, all possible concepts are divided into forty Genera, which are each divided into several “Differences”, which are further divided into Species.

Each Genus comes with a two-letter code, so in this system, any word starting with “Zi” is in the Genus of "beasts". Wilkins then divides “beasts” into six Differences: “Whole footed”, “Cloven Hoofed”, “Non-Rapacious”, “Feline”, “Canine”, and “Egg-laying”. Each of these adds a letter, and then each species gets another letter after that. So all feline beasts start with “Z-I-P”, which is why lion is Zipa, cat is Zipi, and the most famous feline beast of all, the beaver, is Zipyi.

You may not have heard of Wilkins’ Philosophical Language, but you’ve probably heard the parody by Borges. In his short essay, “The Analytical Language of John Wilkins”, Borges invents “a certain Chinese encyclopedia entitled Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge” that divides all animals into different categories. You know the list:

(a) those that belong to the Emperor; (b) embalmed ones; (c) those that are trained; (d) suckling pigs; (e) mermaids; (f) fabulous ones; (g) stray dogs; (h) those that are included in this classification; (i) those that tremble as if they were mad; (j) innumerable ones; (k) those drawn with a very fine camel’s-hair brush; (l) etcetera; (m) those that have just broken the flower vase; (n) those that from a distance resemble flies.

So some of this metaphysics was more successful than others. But all of it was serious — John Wilkins wasn’t some nut, he was one of the founders of the Royal Society. Without him, there would be no science as we know it today. And all of it was metaphysical.

What is a Metaphysics

Ok hold up, let’s go back: what exactly is metaphysics? The term is a little hard to pin down, and there are a few different ways you can try to define it.

One answer is academic: Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that deals with the basic structure of reality. This includes the nature of existence, and the features that all entities have in common.

That answer is kind of dry, so here’s an answer from a Sci-Fi author. Seriously, I think this is a great definition from Neal Stephenson. He says,

A straightforward way of defining metaphysics is as the set of assumptions and practices present in the scientist’s mind before he or she begins to do science. There is nothing wrong with making such assumptions, as it is not possible to do science without them.

A more prosaic definition is that metaphysics is about categories. When you look at the universe, you have to divide it into categories, you know, dog, tree, car, rhombus, et cetera. And sometimes we decide that our categories are wrong, that a whale isn’t a kind of fish, but rather more of a very large, very wet dog. When we think about these issues of categorization, that’s metaphysics.

But “categories” is not quite right, since categorization is about dividing up the things that we already believe in. Metaphysics is a little deeper — it’s also about what sorts of entities the universe does and does not contain in the first place.

You can’t divide microscopic particles into different categories until you believe that there are microscopic particles at all. You can’t divide infectious diseases into categories based on the infectious agent until you believe that diseases can be caused by things like bacteria and viruses, and you can’t do it at all without concepts like “disease”. So metaphysics is about categories, but also about what kinds of things there are to categorize in the first place.

Victims of our own Success

You don’t hear about metaphysics all that much anymore. And I worry that our successes have made us think that metaphysics isn’t important.

We’ve gotten satisfying answers to many of the metaphysical questions we started out with. We have a periodic table for our elements, a quantum model for our physics, cell theory for our medicine, and DNA for our biology. The success of these questions makes people assume that metaphysics is behind us. We think we slew that dragon, that we can beat these swords into plowshares, and spears into pruning hooks.

But we shouldn’t let our guard down yet. The answers we’ve come up with are definitely useful. In some sense, they may even be correct. I’ll leave that question to philosophy hour. But we can’t forget that they are human inventions, and like all human inventions, they may be incorrect.

We keep the periodic table because it works. And maybe it will work forever, in which case, great, fundamental questions of chemistry over. But if we eventually found some place where it stopped making sense, well, we would need to throw it out. If that day comes, we should make sure we remember how to tackle these questions. This used to be a skillset at the heart of science. If you wanted to hack it as a chemist in the 1780s, you needed to be able to think about metaphysics. But we no longer think this skill is important so we don’t teach it.

We now have some kind of answer for all the metaphysical questions someone might ask. What is matter, what is heat, what is light, what is a species, et cetera. And our answers for most of these questions haven’t changed in our lifetimes, so they can seem like they’re final. But having an answer is very different from having the right answer. And just because an answer has stuck around for a while doesn’t mean it’s the right one. We should be much more paranoid.

Metaphysics seems fake to us because we think we live at the end of scientific history, but it was all very real for the scientists of just a few generations ago. If you lived through the turn of the century, you saw your metaphysics overturned several times.

In the 1880s, atoms were indivisible, physics was deterministic, and space and time were both absolute. Fast forward to the 1920s, and all of that has changed. Atoms are no longer indivisible, they’re made up of smaller subatomic particles. In fact, atoms are mostly empty space. Physics is no longer deterministic clockwork, quantum mechanics has made it all probability. Space and time are no longer absolute, they’re relative. And guess what, they’re distorted by mass. That’s metaphysics.

And that’s just a sample of the chaos of that era. If you were a mathematician, you lived through Frege, Russell, Hilbert, Gödel, and Turing. The last few decades of the 19th and first few decades of the 20th century were a wild time to be a scientist, or to be a human being in general. Let’s not forget the massive changes in political science! You couldn’t just take the nature of the world for granted, couldn’t assume that metaphysical questions were all settled, because you had seen your metaphysics get trashed over and over again.

There’s a passage I really like from Albert Einstein. It’s a couple lines from his 1916 obituary for physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach,1 one of Einstein’s personal heroes. He says,

Concepts that have proven useful in ordering things easily achieve such authority over us that we forget their earthly origins and accept them as unalterable givens. … The path of scientific progress is often made impassable for a long time by such errors. Therefore it is by no means an idle game if we become practiced in analysing long-held commonplace concepts and showing the circumstances on which their justification and usefulness depend … Thus their excessive authority will be broken. They will be removed if they cannot be properly legitimated … or replaced if a new system can be established that we prefer for whatever reason.

As much as we would like to, we can’t escape from metaphysics. We live in an age that no longer believes in metaphysics, but even that can’t stop it, you can’t get away from it.

Many of you probably will have strong opinions about this one: is Pluto a planet, or not?2 This isn’t quite as profound a question as the ones raised by Einstein and Rutherford, but it’s still metaphysical. We have to carve up the world in some way, have to draw category boundaries somewhere, but as much as we would like to believe that this is a rational and not at all a political question, as much as we would like to believe that there are objective answers to these carvings, there are not.

Outstanding Metaphysics

Let me give you a few examples besides Pluto.

#1: For years, we’ve classified cancers by the location they appear in the body. And you probably still find it natural to talk about breast cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer. But lately, oncologists have started classifying cancers based on the genetic mutations that caused them (e.g. BRAF V600) rather than the location where they first show up. So instead of saying, “you have lung cancer,” a doctor might now say, “you have cancer with this specific genetic mutation, and it happens to be in your lung.”

It turns out that trying to understand cancer cells in terms of “what part of the cell is malfunctioning?” is a better approach than trying to understand the cells in terms of “what organ did we find them in?” How a tumor behaves and how it responds to treatment usually has more to do with the mutations that created it than what part of the body happened to house the cells that developed those mutations. Two patients with “breast cancer” might benefit from very different treatments, while two patients with tumors in different parts of the body might nevertheless benefit from the same treatment. We’re finding that it’s better to carve up this part of the world based on mutation than based on location.

#2: When astronomers look at the universe, they find two surprises. First, it’s clumpier than it should be. Galaxies stick together more than the gravity from visible matter can explain. Second, it’s expanding faster than it should be, as if some unseen force is pushing everything apart. These are weird and they also seem like they contradict each other: more gravity on one hand, more repulsion on the other.

To explain this, some physicists have come up with the idea of "dark matter", secret mass that could explain the clumping. But this mass would have to not emit, absorb, or reflect light. And they came up with "dark energy", which would explain why everything is flying apart.

New entities with strange properties? That’s metaphysics. And whether or not dark matter and dark energy end up being a good answer, it’s clear that something is missing from the standard model, so metaphysics is needed here one way or another.

#3: Medicine loves to diagnose and carve up the world of human health into different categories, but medical metaphysics is a mess. What counts as a disease, and how we define it, are hotly debated and unstable over time. Remember that “syndrome” means “collection of symptoms that go together but we don’t know why”.

There’s no telling if most of our diagnoses will still be recognizable 100 years from now, and lots of evidence they won’t, in part because most of our diagnoses from 100 years ago aren't recognizable now. To take just one example, there are signs that what we call “rheumatoid arthritis” may turn out to be more than one disease.

And forget about nutrition. Did you know that “Vitamin E” is actually a family of eight different compounds, four tocopherols and four tocotrienols? Plus a ninth synthetic compound, tocofersolan?

Psych Me Out

The younger a science is, the more likely it hasn't gotten good answers to its basic metaphysical questions. And the less you have a working answer to these questions, the more important metaphysics becomes.

So sure, I’m gonna call out economics, sociology, and yes, even medicine. Blocked. Blocked. Blocked. None of you are free of metaphysics.

But I think this is especially important in my home field of psychology. Psychology has a lot of problems, and we usually try to solve them by taking better measurements, or by being extra rigorous in our stats and methods. But taking better measurements doesn’t help when you’re asking meaningless questions, and it’s easy to ask meaningless questions when your metaphysics is all confused. The replication crisis led to a focus on improved methodology: pre-registration, better statistical practices, larger sample sizes. But this doesn't address conceptual weakness.

The easy example is mental health diagnoses. Almost everyone suspects that depression, anxiety, OCD, all these categories are poorly formed. There’s probably more than one kind of depression; or maybe depression is the wrong concept entirely, we should toss it out and start over from scratch.

Again I feel like we’re a victim of our own success here. We have other lists, like a list of chemical elements. People see a list of diagnoses and assume that it’s just as good.

The periodic table and the DSM are both human inventions, but people take the wrong lesson from this. It shouldn’t make you trust the DSM more, it should make you trust the periodic table less. Both of them are up for negotiation at any time. The difference is that the periodic table has so far resisted attempts to find better alternatives. The DSM survives only because we haven’t found a good alternative to rally around, and even so, it changes all the time.

Mental health categories are more like the problems of categorization in medicine. The debate is metaphysical, but it’s mostly about where to draw the lines. But there are also more fundamental questions open in psychology, the kind of profound metaphysics that we haven’t touched in a long time.

Like, what is an emotion? We use a lot of words casually when we’re talking about the mind — nouns like thought, memory, emotion, even “mind” itself, verbs like perceive, think, recall, remember, interpret. These are all very familiar. But medicine used to talk about melancholic and sanguine humors, and chemistry used to talk about four elements and three principles. Those were familiar too.

Thank you.

Unfortunately I've never been able to find the full obit. If someone could point me to it, that would be dope.

For more about Pluto, I recommend this paper and other work from Phil Metzeger.

I agree this is a such an important topic. Thanks for a great piece. Too many people seem to have the view that our fundamental ontological categories are somehow given.

My presocratics philosophy professor used to say that metaphysics is the answer to the question, “what is there, really?” And epistemology is “how do you know?”

The same prof said there are really only two metaphysical answers. Parmenides thought that there is only one thing and Democritus thought that there were infinite things. All metaphysics since then is just a version of one or the other.

This is so, so, so important. Thank you for making such a clear case for the importance of metaphysics and our neglect of it.

The consequences of “conceptual weakness" in medicine and even more so in psychology will turn out to be seen as devastating a few decades from now. I honestly believe that the implicit, misguided metaphysics of psychology has played a central role in shaping today's fractured society. It is baked into how everyone sees/experiences themselves and one another, and it separates us from what I believe will turn out to be a much more vibrant and generative natural potential than we're able to engage right now, trapped as we are in this primitive structure.

Let me share an example of the weakness that comes from my work investigating the actual, subjective experience of what we commonly call “feeling.” Currently, we think of feeling as existing in two places: the somatic sensations of the body and the cognitive interpretations of those sensations in the situational context of our lives. However, if we actually examine what exists in the actual experience of feeling, we find something very different that does not exist in our current maps.

If you turn attention toward the experience of a specific feeling state and invite a comparison to materiality — substance qualities, temperature, movement, that sort of thing — you get very tangible, detailed, precise “readings” of the experience. I use a series of potent questions to direct attention in this way, and the map that’s generated in response to those questions feels tangibly, palpably “real” to the person experiencing that feeling state. Not only that, but once the map is generated, it can be used to directly interact with the feeling state by intentionally changing the virtual material properties. Changing a hard, heavy solid to something softer and lighter directly and instantly changes the state. Changing it back changes the actual feeling back to its original state.

Where is this in our current conceptual frameworks? Nowhere. And yet, it is baked into our language, everywhere, all over the world. We constantly use references to materiality to describe how we feel.

This is an example where our actual inner experience differs from the implicit metaphysics of the “science” of psychology, and the effect is that we pay much less attention to our actual feeling experience and lock our awareness into the zones of cognition and soma. And the results of that are really, really bad for everyone.