Book Review: The Great Gatsby

Novels for when you survive The Great War and/or are about to turn 30

The Great Gatsby was published in 1925, and I recently happened to pick it up for a re-read, so in these last few hours of 2025 I thought it might be nice to try to sneak a 100th-anniversary review in under the wire.

I liked The Great Gatsby a lot more on my second read-through than I did when I read it in high school. I think it deserves its status as a Great American Novel. I’m also grateful to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s editor, Maxwell Perkins, who convinced him that “The Great Gatsby” was a better and more marketable title than his original idea, “Trimalchio in West Egg”.1

But my main takeaway is that I can’t believe that we make everyone read this novel in high school. It’s great literature, but I don’t know if teenagers can be expected to relate just yet, because The Great Gatsby is a book about what it feels like to survive World War I and then turn 30.

A quick recap of the plot: It’s 1922, and Nick Carraway has just moved to New York City. He is a Yale graduate and a World War I veteran. Lacking any idea of what to do with his life, he becomes a bond salesman, and rents “a weather-beaten cardboard bungalow at eighty a month” on Long Island. But he never shows any interest in the job; it’s a fantasy. He buys “a dozen volumes on banking and credit and investment securities” but never reads them. And he acts a bit like he’s roughing it, but he’s not. “Father agreed to finance me for a year,” he reports.

Nick starts making connections. Daisy Buchanan, his second cousin once removed, and her husband Tom Buchanan, an enormously wealthy Yale football star who Nick already knows from college, happen to have just moved from Chicago to a mansion across the bay, for no apparent or particular reason. Nick is soon invited to their house, where he meets flapper and golf champion Jordan Baker, and learns all kinds of nasty details about Tom and Daisy — like that Tom has a mistress, the wife of a local mechanic.

Back at the bungalow, Nick’s neighbor is the enigmatic millionaire Jay Gatsby, who spends all summer hosting gigantic parties. For a long time Nick watches from the outside, but one morning he receives an invitation and ends up meeting Gatsby at the party.

Just like Nick, Gatsby is a WWI veteran. The first thing he asks Nick is, “Weren’t you in the First Division during the war?” and they talk for a moment about “some wet, grey little villages in France”.

The first time they have a serious heart-to-heart, Gatsby unloads on Nick about how suicidal he was:

“Then came the war, old sport. It was a great relief, and I tried very hard to die, but I seemed to bear an enchanted life. I accepted a commission as first lieutenant when it began. In the Argonne Forest I took the remains of my machine-gun battalion so far forward that there was a half mile gap on either side of us where the infantry couldn’t advance. We stayed there two days and two nights, a hundred and thirty men with sixteen Lewis guns, and when the infantry came up at last they found the insignia of three German divisions among the piles of dead. I was promoted to be a major, and every Allied government gave me a decoration—even Montenegro, little Montenegro down on the Adriatic Sea!”

Through Jordan, Gatsby reveals that he has a history with Daisy. They met in 1917 and fell in love, but when Gatsby went off to war, Daisy married Tom instead, though she almost backed out at the last moment when she received a mysterious letter. They enlist Nick in a conspiracy to reunite Gatsby and Daisy, who meet at his bungalow and begin having an affair. But this isn’t enough for Gatsby. “He wanted nothing less of Daisy,” reports Nick, “than that she should go to Tom and say: ‘I never loved you.’”

The Great Gatsby is about turning 30, and it isn’t exactly subtle. The climax of the novel comes in a suite in the Plaza Hotel, where Gatsby insists that Daisy renounce Tom to be with him instead. “Your wife doesn’t love you,” He tells Tom. “She’s never loved you. She loves me.” But Daisy insists that she loves both of them, and in the end she rejects Gatsby in favor of Tom. At exactly this moment, Nick Carraway, the narrator, remembers that he has just turned 30:

“Nick?” He asked again.

“What?”

“Want any?”

“No… I just remembered that today’s my birthday.”

I was thirty. Before me stretched the portentous, menacing road of a new decade.

It was seven o’clock when we got into the coupé with him and started for Long Island. Tom talked incessantly, exulting and laughing, but his voice was as remote from Jordan and me as the foreign clamour on the sidewalk or the tumult of the elevated overhead. Human sympathy has its limits, and we were content to let all their tragic arguments fade with the city lights behind. Thirty—the promise of a decade of loneliness, a thinning list of single men to know, a thinning briefcase of enthusiasm, thinning hair. But there was Jordan beside me, who, unlike Daisy, was too wise ever to carry well-forgotten dreams from age to age. As we passed over the dark bridge her wan face fell lazily against my coat’s shoulder and the formidable stroke of thirty died away with the reassuring pressure of her hand.

So we drove on toward death through the cooling twilight.

The Great Gatsby is definitely about men trying to paper over their fears of aging and dying by trying to capture an elegant woman. But this feeling is not exclusive to the gentlemen. When they hear the sounds of jazz being played for a wedding in the hotel below, Daisy remarks, “We’re getting old. If we were young we’d rise and dance.”2

I didn’t ever survive World War I, but as someone who turned 30 a few years ago, I enjoyed this book. But I can’t believe we expect high schoolers to appreciate it, much less understand it. I didn’t understand this book the first time I read it, and I don’t think my classmates did either. The whole thing must have gone over our heads.

In retrospect, the things we must have missed are kind of astonishing. Jokes and references about the book mostly run along the lines of “Gatsby parties”, or saying “old sport” over and over again. Now “old sport” does admittedly appear in the novel a total of 45 times, I counted. But the book is so much more than that.

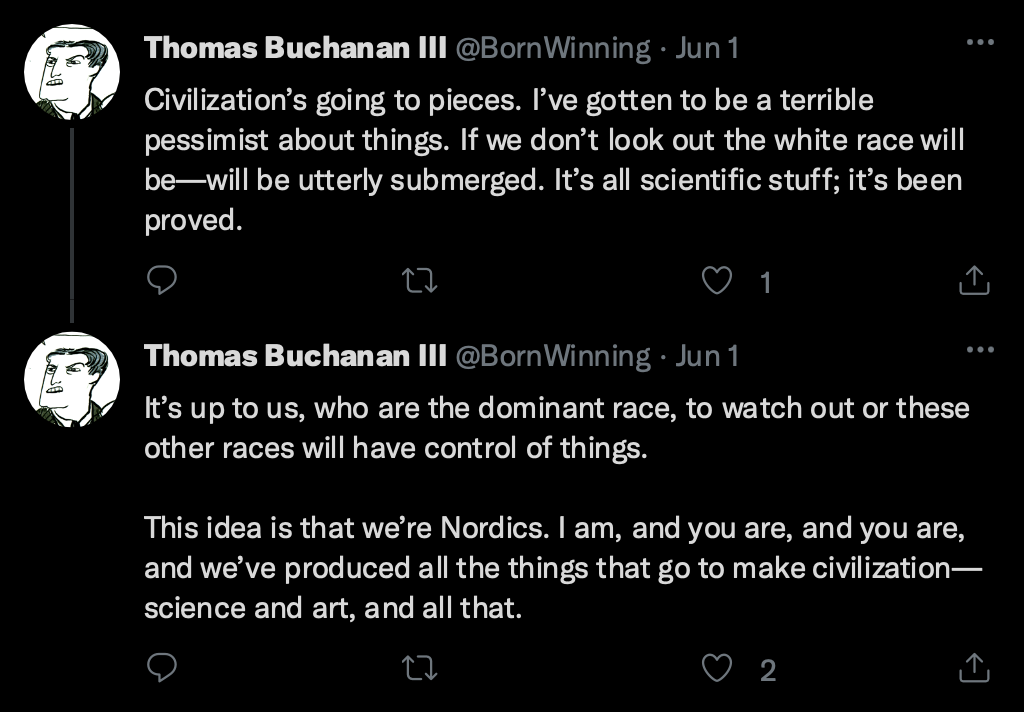

I was surprised during my re-read to discover that Daisy’s husband Tom is a turbo-racist:

“Civilization’s going to pieces,” broke out Tom violently. “I’ve gotten to be a terrible pessimist about things. Have you read The Rise of the Coloured Empires by this man Goddard?”

“Why, no,” I answered, rather surprised by his tone.

“Well, it’s a fine book, and everybody ought to read it. The idea is if we don’t look out the white race will be—will be utterly submerged. It’s all scientific stuff; it’s been proved.”

“Tom’s getting very profound,” said Daisy, with an expression of unthoughtful sadness. “He reads deep books with long words in them. What was that word we—”

“Well, these books are all scientific,” insisted Tom, glancing at her impatiently. “This fellow has worked out the whole thing. It’s up to us, who are the dominant race, to watch out or these other races will have control of things.”

“We’ve got to beat them down,” whispered Daisy, winking ferociously toward the fervent sun.

“You ought to live in California—” began Miss Baker, but Tom interrupted her by shifting heavily in his chair.

“This idea is that we’re Nordics. I am, and you are, and you are, and—” After an infinitesimal hesitation he included Daisy with a slight nod, and she winked at me again. “—And we’ve produced all the things that go to make civilization—oh, science and art, and all that. Do you see?”

There was something pathetic in his concentration, as if his complacency, more acute than of old, was not enough to him any more.

This appears to be Tom’s new obsession. Nick remarks that, “the fact that [Tom] ‘had some woman in New York’ was really less surprising than that he had been depressed by a book. Something was making him nibble at the edge of stale ideas as if his sturdy physical egotism no longer nourished his peremptory heart.” Even when he’s fighting with Gatsby over Daisy’s love, Tom’s thinking jerks in this direction, and he says, “Nowadays people begin by sneering at family life and family institutions, and next they’ll throw everything overboard and have intermarriage between black and white.”

Either I missed this entirely when I read it in high school, or I totally forgot it in the years since. Even so, that’s kind of surprising; I remembered lots of other details about the book! How did I miss that?

Do you remember Meyer Wolfsheim, Gatsby’s Jewish friend, mentor, and business partner? Do you remember that near the end of the novel, when Nick goes to see Wolfsheim to invite him to Gatsby’s funeral, the name of Wolfsheim’s business front is “The Swastika Holding Company”?

The morning of the funeral I went up to New York to see Meyer Wolfsheim; I couldn’t seem to reach him any other way. The door that I pushed open, on the advice of an elevator boy, was marked “The Swastika Holding Company,” and at first there didn’t seem to be anyone inside. But when I’d shouted “hello” several times in vain, an argument broke out behind a partition, and presently a lovely Jewess appeared at an interior door and scrutinized me with black hostile eyes.

This is some weird accidental oracle shit on Fitzgerald’s part. At the time, the swastika didn’t have antisemitic connotations to most people (though the Nazi party had adopted the swastika in 1920). It was instead a popular symbol of luck and success, “much like the four leafed clover”, and probably was intended to give Meyer Wolfsheim an exotic, oriental air, just like how his cuff buttons are made of “oddly familiar pieces of ivory”, which Wolfsheim calls attention to and reveals as the “finest specimens of human molars”.

But again, it’s very strange that I don’t remember this standing out to us as high schoolers. You’d expect we would pick up on the irony of this one Jewish character having a company named after the swastika. But apparently not.

But even if they don’t fully appreciate it, it’s probably good to have the young’uns read this book, and not just because it is one of the last touchstones giving us a shared national identity. Not even because it might encourage them to try calling each other “old sport” over tater tots in the cafeteria.

History rhymes more than I would like it to. So far we have dodged having another great war, but we had our own major pandemic in 2020 to mirror the Spanish Flu of 1918, and I worry we are facing a new jazz age, except this time without the comfort of actual advancements in jazz. Too many of the same social issues are coming around again; Tom would fit in disconcertingly well on the more racist parts of Twitter.

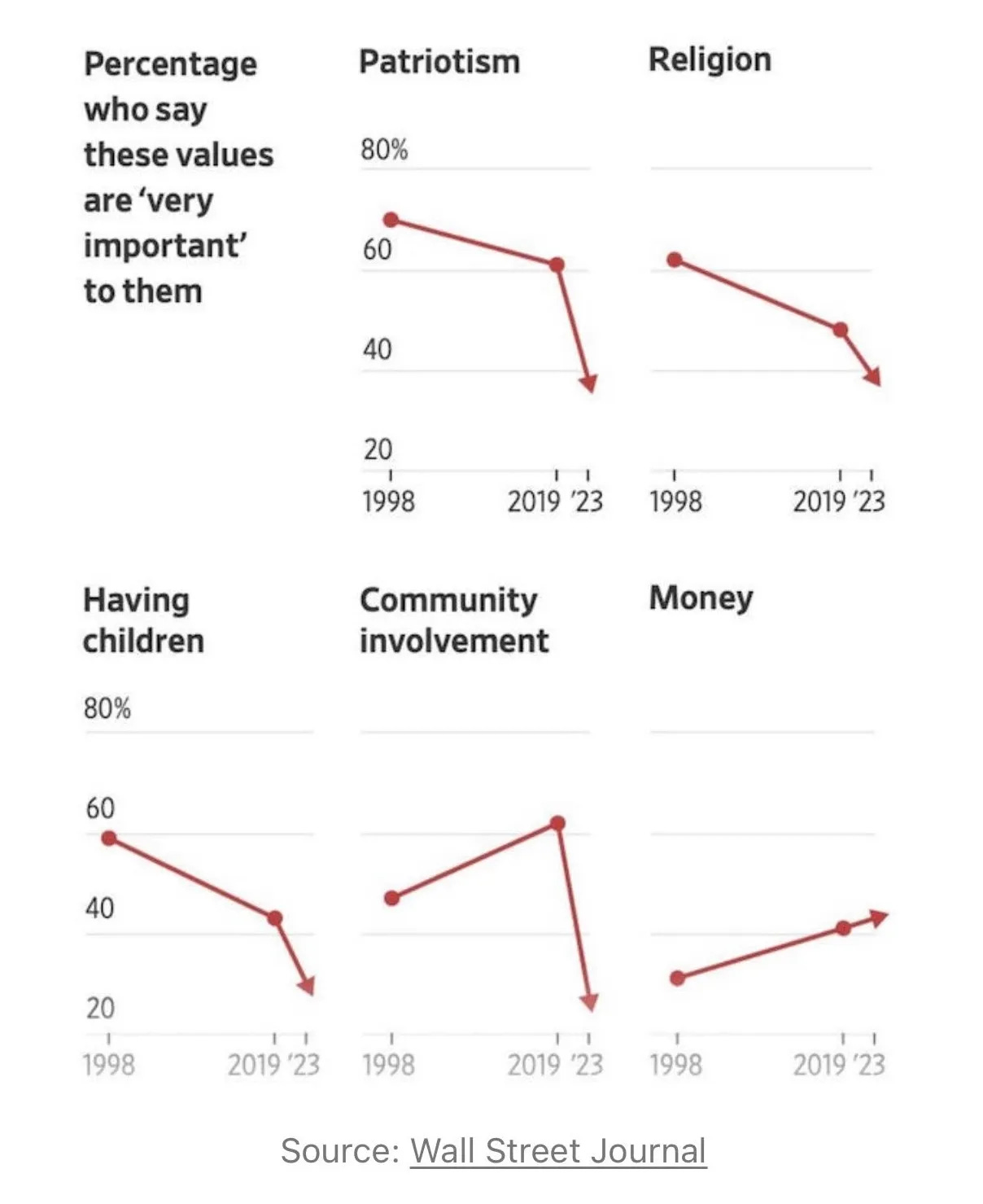

I was struck by Wikipedia’s description that: “In Fitzgerald’s eyes, the [Jazz Age] represented a morally permissive time when Americans of all ages became disillusioned with prevailing social norms and obsessed with pleasure-seeking.” When I saw that, I thought of this Wall Street Journal poll from 2023:

Everyone remembers the last line of The Great Gatsby: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” But I find myself more drawn to the paragraphs just before that.

“His dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.” I wonder if Fitzgerald was self-aware about the fact that this novel was to be published on the eve of the 150th anniversary of the United States.

Happy 2026.

From Wikipedia: “Trimalchio is a character in the 1st-century AD Roman work of fiction Satyricon by Petronius. He features as the ostentatious, nouveau-riche host in the section titled the ‘Cēna Trīmalchiōnis’ (The Banquet of Trimalchio, often translated as ‘Dinner with Trimalchio’). Trimalchio is an arrogant former slave who has become quite wealthy as a wine merchant. The name ‘Trimalchio’ is formed from the Greek prefix τρις and the Semitic מלך (melech) in its occidental form Malchio or Malchus. The fundamental meaning of the root is ‘King’, and the name ‘Trimalchio’ would thus mean ‘Thrice King’ or ‘greatest King’.”

The Great War is a major influence on the men in this story, but it goes largely unstated in part because it would have been obvious to readers at the time. For the ladies, it’s easy for the modern reader to miss the fact that the 19th Amendment was passed in 1920. Jordan and Daisy can vote, but at the time of the story they’ve only had that legal right for two years.